The original Crabbet/Maynesboro/Kellogg mare families: Foundation of a unique North American gene pool one hundred years in the making

Rick Synowski © Copyright 1992

Used by permission of Rick Synowski. First published in the CMK Heritage Catalogue Volume III

This treatment reflects the CMK dam line picture before the 1993 revision of the CMK Definition. — MB

While CMK Arabian horses have come to represent a minority breeding group today, CMK foundation mare lines hold fast to their international domination of lists of leading dams of champions. Their production records, some accomplished by mares now deceased, may never be equalled. The character, type and breeding of such celebrated mares must inevitably be diminished and disappear when outcrossing to stallions of other breeding groups predominates.

Veteran horsewoman Faye Thompson, whose father Claude Thompson introduced the Arabian horse into Oregon nearly 60 years ago, observes that “modern Arabian horses are good horses, but they’ve lost that classic, desert look that used to excite me so. Modern horses don’t get me excited the way the old ones did” [CMK Record, Spring 1989].

It is to be hoped the classic desert look which so excited the observer does not disappear, but may be perpetuated on some scale as CMK mares produce within the CMK breeding group. Perhaps the realization of the unique history behind these mares will contribute to this end.

Imported in 1888: *Naomi

THE FIRST ARABIAN MARE TO come to North America and leave modern descent, and the oldest mare in the Arabian Horse Registry of America, is *Naomi, foaled in England in 1877. Her sire and dam YATAGHAN and HAIDEE were brought from the desert by Capt. Roger Upton. Randolph Huntington, America’s earliest breeder of Arabian horses still represented in modern lines, imported *Naomi in 1888. In 1890 *Naomi foaled the fine chestnut colt ANAZEH, the first Arabian bred and born on American soil to leave modern descent. ANAZEH was sired by *Leopard, the grey Arabian stallion presented by Sultan Abdul Hamid II of Turkey to General U.S. Grant in 1878.

A mare with many firsts to her credit, though perhaps not of the show ring variety, *Naomi was photographed here at age 18, standing behind the strapping 13-day-old Khaled, her eighth of ten foals. As an individual *Naomi must have pleased Randolph Huntington, who by this time was enjoying no small recognition as one of America’s leading breeders of light horses. Huntington would build his entire Arabian program around this single mare, and thus *Naomi would make a far-reaching contribution to the development of a North American Arabian gene pool via her high-quality descendants.

Perhaps the most important of *Naomi’s tail-female descendants was to be the Manion-bred IMAGIDA, dam of the illustrious *Raffles daughters GIDA and RAFGIDA and two sons also by *Raffles, IMARAFF and RAFFI. Another distinguished female line was founded by the straight Maynesboro MADAHA. *Naomi’s descent from both sons and daughters also included the likes of RAHAS, GHAZI, RABIYAT, GHAZAYAT, Abu Farwa, ALLA AMARWARD and Aurab, just to name a few of the famous ones. *Naomi’s sons and daughters were among the finest horses of their time, and their descendants continue to be so regarded.

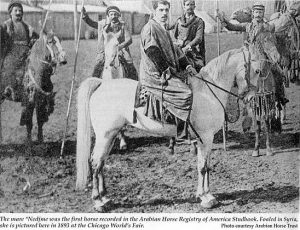

1893: *GALFIA and *NEJDME

IN 1893, BY SPECIAL ARRANGEMENT with Abdul Hamid II, Sultan of the Ottoman Empire, 45 Arabian horses were brought from Syria for exhibition at the Chicago World’s Fair. The Hamidie horses, so named for the Hamidie Hippodrome Company which sponsored the exhibition, were beset by a series of disasters. Financial ruin of the company and a fire left 28 horses to be auctioned off.

Only three mares of the entire group would be given the opportunity to breed on. In 1894 Peter Bradley purchased the mares *GALFIA and *PRIDE. The third mare, *NEJDME, was purchased by J.A.P. Ramsdell. *GALFIA would be the first of the three to produce with her 1895 colt, MANNAKY JR. by the Hamidie stallion *MANNAKY. The following year *GALFIA again foaled to *MANNAKY and the filly ZITRA was to establish *GALFIA’s tail female line into modern descent.

In 1898 *NEJDME established the third American mare line with the birth of NONLIKER, sired by Ramsdell’s Ali Pasha Sherif stallion *SHAHWAN. Unfortunately NONLIKER was the only foal of the magnificent *SHAHWAN to breed on in America. That *SHAHWAN left scant descent at Crabbet prior to his importation was to be regretted by the Blunts as well, given the breeding performance of his daughter YASHMAK. NONLIKER was joined by younger half-sisters NANSHAN (1902) and NANDA (1905); the *NEJDME lines of DAHURA and LARKSPUR came to be particularly highly prized.

The third Hamidie mare bred on but not in tail female. *PRIDE produced just one registered foal, the 1902 mare SHEBA sired by MANNAKY JR. SHEBA would leave an important mark on the breeding program of Albert W. Harris in her sons NEJDRAN JR (by *NEJDRAN) and EL JAFIL (by *IBN MAHRUSS), sire of Harris’ noteworthy EL SABOK.

Much of the identifying information on the Hamidie horses, including the original authentication, has been lost, presumably in the fire. Bits and pieces of information from letters and newspaper articles have surfaced over the years. Some of the information coming down is conflicting regarding strains and birthdates, if not the outright identities of some of the horses. What we do know is that the horses which bred on did so extremely well.

1900: BASILISK

IN 1900 THE FIRST CRABBET MARE came to America in the person of the BASILISK granddaughter *BUSHRA. She is registered as imported from the Crabbet Stud by “Mr. Eustis” but almost certainly went directly to Randolph Huntington’s ownership and produced her American offspring for Homer Davenport.

Wilfrid Blunt considered the family of BASILISK to be one of the best of their early desert importations. Later, the American breeder Spencer Borden noted the BASILISK mare line as the “best blood in the world.” The BASILISK family would be well represented among the early imports. *BUTHEYNA, *BARAZA and *BATTLA followed *BUSHRA.

The BASILISK female line died out at Crabbet, though it continued to England from the line established by BELKA at the Courthouse Stud. In America the line flourished notably from the Maynesboro mare BAZRAH.

1905: WILD THYME and RODANIA

SPENCER BORDEN CAME UPON the scene at the turn of the century. His contribution to the Arabian horse in America as an importer, breeder and author during these early days was to be monumental. In 1898 Borden had imported *SHABAKA from England, a mare by the desertbred MAMELUKE and out of KESIA II, imported en utero from the desert. *SHABAKA was not to establish a female line but her influence was realized in a highly valued son, SEGARIO. The KESIA mare line would in fact never become established here, but was represented again in Borden’s 1905 import, *SHABAKA’s half-brother *IMAMZADA, and in the 1924 Harris import *NURI PASHA [ex RUTH KESIA].

In 1905 Borden imported two fillies from the Hon. Miss Ethelred Dillon and introduced the WILD THYME mare line to breed on in America. Borden’s yearling *MAHAL and weanling *NESSA were both daughters of the Crabbet mare RASCHIDA (Kars x Wild Thyme). Like BASILISK’s, WILD THYME’s family died out early at Crabbet, but it was ably perpetuated by both *MAHAL and *NESSA in this country.

It was a stroke of genius that, also in 1905, Borden introduced the RODANIA female line to America with his importation of the dowager queen mother of Crabbet, *ROSE OF SHARON. Borden’s coup in obtaining the most celebrated of Crabbet’s early matrons must be considered in light of her unparalleled international influence.

The RODANIA daughters spread the influence of Crabbet breeding to virtually every other Arabian horse breeding base in the world. *ROSE OF SHARON’s mare line would carry forward in American breeding by her tail female descendants imported later from Crabbet. Her uniquely American contributions to the breed came via her son *RODAN and daughter ROSA RUGOSA, dam of the important Maynesboro sire SIDI.

The two remaining branches of RODANIA’s family were brought to America later and also became firmly established here. The RODANIA daughter ROSEMARY is represented by *ROKHSA, imported in 1918 by W.R.Brown, *RAIDA, imported in 1926 by Kellogg, *RISHAFIEH, imported in 1932 by Selby, and *KADIRA, imported 1939 by J.M. Dickinson. The ROSE OF JERICHO branch was established by the 1926 Kellogg imports *ROSSANA, *RASIMA and *RASAFA, and the 1930 Selby ones *RASMINA and *ROSE OF FRANCE.

1906: *WADDUDA, *RESHAN, *ABEYAH, *URFAH, *WERDI, *HADBA

IN 1906 HOMER DAVENPORT imported 27 Arabian horses directly from the desert. This importation would be the largest genetic contribution unique to American Arabian horse breeding. Six of Davenport’s desert mares would establish mare lines, and each would be represented on the leading dams of champions lists. For many years the leading dam of champions, BINT SAHARA, and her runner-up daughter FERSARA, are of *WADDUDA’s line. SAKI, whose champion produce record would come to equal BINT SAHARA’s, was of *WERDI’s family.

As in the case of each of these mares, Davenport breeding blended wonderfully well with that of other early CMK sourcess, the result being realized in some of the best representatives of the breed in history. Interestingly, some of Davenport’s desert sources were the same breeders from whom the Blunts had purchased foundation stock nearly 30 years earlier. The success Davenport, and later W.R.Brown, Harris, Kellogg, Hearst and Selby realized in combining Davenport and Crabbet breeding represented in some cases a recombining of lines derived from the same desert sources.

Davenport mare lines survive both in straight Davenport breeding programs and inextricably within the larger CMK breeding group. Their contribution of classic desert type and quality can still readily be identified.

1909: BINT HELWA

APART FROM HOMER DAVENPORT, there was no one to compare to the spirited patronage of Spencer Borden for the Arabian horse in America at the turn of the century. Borden’s visits to the Crabbet Stud and his lively correspondence with Lady Anne Blunt were to gain him respect and favor in securing some of the best individuals of that Stud. And so in 1909 Borden would again bring a grande dame of Crabbet to American shores, the Ali Pasha Sherif bred *GHAZALA, daughter of the Crabbet family foundress BINT HELWA.

BINT HELWA’s line was a third to take hold in America but die out at Crabbet. And take hold it did in the two illustrious *GHAZALA daughters, GULNARE and GUEMURA. Two other branches of the BINT HELWA family would later provide foundation mares to American CMK breeding in *HAMIDA, *HAZNA and *HILWE.

1910: DAJANIA and *LISA

THE NEXT YEAR A FIFTH Crabbet family line would reach America in the DAJANIA mare *NARDA II, imported by F. Lothrop Ames. *NARDA II, a daughter of NARGHILEH, was purchased in foal to RIJM and the next year foaled *NOAM, a three-quarters sister to *NASIK, *Nureddin II and NESSIMA.

The DAJANIA family would be greatly distinguished at Crabbet and in America as producers of some of the greatest sires in the history of the breed: the aforementioned *NASIK and *Nureddin II, and NASEEM, INDIAN GOLD, *NIZZAM, INDIAN MAGIC, *SERAFIX, ELECTRIC SILVER and *SILVER DRIFT. In America the DAJANIA line sires included INDRAFF, RAPTURE and AARAF.

Later *INDAIA was imported by Roger Selby and *INCORONATA by Kellogg, bringing the imported family of DAJANIA mares to just four.

Also in 1910, the mare *LISA was imported by C.P.Hatch. She was listed as having been “bred in the desert” and registered as black. *LISA’s family line survives via one daughter, ALIXE by *HAURAN. ALIXE’s breeder was Warren Delano of Barrytown, NY. ALIXE in turn produced three daughters by JERREDE (*Euphrates x *Nejdme), and of these JERAL and NARADA bred on.

1918: FERIDA and SOBHA

THE MAYNESBORO STUD IN Berlin, NH was founded in 1912 by William Robinson Brown. Brown’s foundation stock was acquired in the beginning from other American breeders. It was, in fact, via Maynesboro that key links with some of the earliest CMK bloodlines were to be carried forward.

In 1918 Brown made an importation of 17 horses from the Crabbet Stud. Brown’s purchase would be a timely one for CMK breeding in that advantage was taken, purposely or not, of the legal feud between Lady Wentworth and her father Wilfrid Blunt, after Lady Anne Blunt’s death. Certain Crabbet horses were acquired by Brown which might otherwise never have left the Stud. This was especially true of the phenomenal *BERK.

The 1918 Maynesboro importation introduced the FERIDA family to North America in the two-yr-old chestnut filly *FELESTIN. *FELESTIN’s dam FEJR (Rijm x Feluka) also produced the stallions FARIS and FERHAN, sires in turn of the important English breeding horses RISSALIX and INDIAN GOLD.

A second, more prolific, branch of the FERIDA family was established eight years later with the importation of the celebrated FELUKA daughter, *FERDA, by W.K.Kellogg. Ten years after her importation, half the horses at the Kellogg Ranch would be descended from *FERDA, such was the value of this FERIDA line mare.

The 1918 Maynesboro importation also brought a seventh Crabbet family to America in the SOBHA representative, *SIMAWA, a mare who would later become important to the breeding program of Albert Harris. Selby and Kellogg would each make astute importations of SOBHA line mares in *SELMNAB (imported 1930) and *CRABBET SURA (imported 1936).

The most acclaimed branch of the SOBHA family did not reach America until the 1950s. This was the line of Lady Wentworth’s unforgettable SILVER FIRE.

1921 and 1922: *BALKIS II and *KOLA

W.R. BROWN WAS A U.S. ARMY Remount agent, and it was a major purpose of his breeding program that Arabians be bred as suitable mounts for cavalry. It was probably with this in mind that in 1921 and ’22 he imported Arabian horses from France, a country long esteemed for breeding cavalry horses.

Brown’s French importation was in keeping with the tradition of Huntington, Borden, Bradley and Davenport, who touted the utilitarian supremacy of the Arabian horse, promoting the Arabian for American cavalry use.

Two of the French mares would establish mare lines at Maynesboro. The *BALKIS II granddaughter FOLLYAT and the *KOLA daughters FADIH and FATH were broodmatrons which especially earned respect for the contribution of French breeding to the CMK foundation.

1924: QUEEN OF SHEBA

THE SOLE REPRESENTATIVE of the Crabbet family of QUEEN OF SHEBA to breed on in CMK founder lines was *ANA (Dwarka x Amida), imported to America in 1924. *ANA would produce two daughters for her importer Albert Harris. She was later sold to Philip Wrigley for whom she was to produce four more daughters including the notable ADIBIYEH.

*ANA was full sister to *ALDEBAR, bred by H.R.H. the Prince of Wales and imported by Henry Babson.

1928: *NOURA and MAKBULA

AMEEN RIHANI OF NEW YORK imported three Arabians from the desert in 1928, a stallion *SAOUD and two mares, *NOURA and her daughter *MUHA. A thin but well-regarded line was to come from these mares. *NOURA’s family would be famously represented by Margaret Shuey’s elegant matron MY BONNIE NYLON.

Roger Selby’s Crabbet importation of 1928 introduced the MAKBULA family to America in the small-statured, exquiste *KAREYMA. *KAREYMA would prove to be one of Selby’s best purchases from Crabbet, judging by the excellence of her produce. Selby would bring three more representatives of the MAKBULA line to Ohio in 1930 with the importation of *KIYAMA, *JERAMA and *NAMILLA.

1929: *MALOUMA

IN 1929 HERMAN FRANK of Los Angeles imported *MALOUMA, the first of two Egyptian lines to be incorporated into the foundation of CMK breeding. *MALOUMA was purchased by Kellogg for whom she produced the four daughters which carry on her line.

1931: *LA TISA

IN 1931 THE CHICAGO INDUSTRIALIST and philanthropist Charles Crane made a trip to the Middle East and came back with some Arabian horses, gifts from Saudi Arabia’s King Abdul Aziz, who had not met an American before Crane. Crane dispatched a geologist engineer to Arabia in search of oil and water.

This exchange of favors between Crane and the Saudi ruler resulted in ARAMCO’s being established as Saudi Arabia’s petroleum exploration and development partner–a partnership which only too obviously has shaped American foreign policy to this day.

Crane’s two fillies, *LA TISA and *MAHSUDHA, reportedly were of quality and beauty in keeping with the rest of his venture. *LA TISA would establish a family which has carried forward into CMK breeding.

1932: BINT YAMAMA

W.R.BROWN INTRODUCED A second Egyptian mare line to CMK breeding with the 1932 importation of seven Arabians bred by Prince Mohammed Ali of Cairo. All were of the BINT YAMAMA family line, which was perpetuated by the four mares: *RODA and *AZIZA, daughters of NEGMA; *H.H. MOHAMMED ALI’S HAMAMA and *H.H. MOHAMMED ALI’S HAMIDA, both out of the famed NEGMA daughter MAHROUSSA. The Maynesboro Egyptian importation had been made at the same time as Henry Babson’s importation of six horses also from Egypt.

Interestingly, the origins of the Egyptian horses can be traced back in part to Abbas Pasha/Ali Pasha Sherif stock of the Blunt’s day. The exact origin of BINT YAMAMA and her relationship to early Blunt horses is a mystery yet to be solved.

1934: ZULIMA

IN 1934, JIM AND EDNA Draper of Richmond, California brought home five Arabians from Spain. Four of the five were mares, and all of the same female line, that of the Spanish ZULIMA through SIRIA. The elegant grey *NAKKLA was purchased by Kellogg’s and incorporated into that breeding program. The Drapers retained the SIRIA daughters *MECA and *MENFIS (dam of *NAKKLA) and *MECA’s daughter *BARAKAT, breeding them to CMK stallions.

The Draper Spanish mares produced admirably, gaining a place of pride within the CMK tradition. Edna Draper holds the distinction of being the last importer of CMK foundation stock still living.

1947: *NAJWA, *LAYYA, *KOUHAILANE, *LEBNANIAH, *RAJWA, *NOUWAYRA

THE LAST DESERT CONTRIBUTION considered a part of CMK foundation breeding was the Hearst importation of 1947. This was the largest group of Arabians brought directly from the Arabian desert countries since that of Homer Davenport.

The Hearst Ranch had been established with the purchase of Maynesboro stock upon that farm’s dispersal, which included the Maynesboro sires RAHAS, REHAL, GHAZI and GULASTRA. Hearst had also purchased Kellogg stock, bring about a parallel breeding program to that Stud’s.

The Hearst importation included eight mares (*RAJWA was accompanied by her daughter *BINT RAJWA), all but one of which contributed to the CMK breeding tradition.

1953: HAGAR

HAGAR, THE “JOURNEY MARE,” was the Blunts’ second acquisition in the desert, but it took 75 years before her female line reached America to stay. HAGAR was purchased to carry Wilfrid Blunt from Aleppo to Baghdad and back to Damascus on the Blunts’ 1878 journey. She proved admirably up to the task and earned praise from Lady Anne in her journals.

HAGAR was sent to England as part of the foundation of the Crabbet Stud. She was sold to the Hon. Ethelred Dillon for whose Puddlicote Stud HAGAR proved a foundress. The first HAGAR breeding reached America in 1905 via the important Dillon-bred *NESSA’s sire *HAURAN and another HAGAR son, HAIL.

There was still no HAGAR female line in America when hers became another family lost to Crabbet. The line persisted through Miss Dillon’s ZEM ZEM and through HOWA, foundation mare of the Harwood Stud. ZEM ZEM and her daughter ZOBEIDE were left to Borden by Miss Dillon’s will, but left no further registered progeny.

It was not until 1953 that the HAGAR family would reach American shores and be carried on into CMK breeding. This came about when seven mares from Holland’s Rodania Stud (Dr. H.C.E.M. Houtappel) were imported to New York by T. Cremer. The mares were *CHADIGA, *FAIKA, *LATIFAA, *FATIMAA, *RITLA, *LEILA NAKHLA and *MISHKA.

With HAGAR’s line, American breeders had 10 mare families to carry on the Crabbet breeding base.

THESE, THEN, ARE THE ORIGINAL CMK MARE FAMILIES. They have been combined in American horse breeding history to form one genetic legacy uniquely American–CMK. The timeless quality of CMK mares should be obvious to all fanciers of the Arabian horse, but it would appear to fall to a few to recognize that an effort must be made to conserve the identity of these irreplaceable lines for posterity.

This treatment reflected the CMK dam line picture before the 1993 revision of the CMK Definition. — MB