by R.J. Cadranell

from The CMK Record Summer 1989 VIII/I

copyright 1989

In 1791, during the century which saw the writing of great compendiums of knowledge, including Dr. Johnson’s dictionary, James Weatherby published in England what was to become the preliminary volume of The General Stud Book, Containing Pedigrees of Race Horses, &c. &c. From the earliest Accounts… In 1808, after several revisions, appeared the version which has become standard. This documented the pedigrees of a breed of horse which later adopted the name of Thoroughbred. Mr. Weatherby’s stud book demonstrates the Thoroughbred’s descent from numerous Oriental sires and dams. The pedigree of the Thoroughbred stallion ECLIPSE (1764) lists the names of the DARLEY ARABIAN, the LEEDES ARABIAN, the OGLETHORPE ARABIAN, the LISTER TURK, the DARCY YELLOW TURK, the BYERLEY TURK, the GODOLPHIN ARABIAN or Barb, HUTTON’S GREY BARB, and the MOROCCO BARB as ancestors.

The American Stud Book, a.k.a. the Jockey Club Stud Book, first appeared in 1873. Its original complier was S.D. Bruce, and The American Stud Book (ASB) is still the registration authority for Thoroughbreds in this country. Volume I included a chapter for “Imported Arab, Barb and Spanish Horses and Mares.”

Weatherbys issued Volume XIII of the General Stud Book (GSB) in 1877. This volume included a new section, roughly one page in length, for Arabian stock recently imported to the U.K. It was the beginning of modern Arabian horse breeding in the English speaking world. In this volume are Arabians which Capt. Roger D. Upton and H.B.M. Consul at Aleppo, Mr. James H. Skene, were involved in importing for Messrs. Sandeman (including YATAGHAN and HAIDEE, the sire and dam of *Naomi) and Chaplin (including the mare KESIA). GSB Volume XIV (1881) registered the earliest of Mr. Wilfrid and Lady Anne Blunt’s importations for their Crabbet Arabian Stud. Skene had provided crucial assistance to the Blunts, too; Wilfrid Blunt later credited Skene with giving him and his wife the idea for the Crabbet Stud (see Archer et.al., The Crabbet Arabian Stud. p. 34). Skene is perhaps the founding father of Arabian horse breeding in the English speaking world. The preface to GSB Volume XIV expressed the hope that the newly imported Arabian stock might, in time, provide the Thoroughbred with a valuable cross back to the original blood from which it had come. This idea had also been behind the thinking of Upton and Skene.

The Blunts subscribed to this view too. The British racing authorities agreed to hold an Arab race at Newmarket in 1884; the outcome was inconclusive, but Blunt wrote that

“the ultimate result, however, was not I think, as far as Arab breeding in England was affected by it, wholly a misfortune. It convinced me that I was on wrong lines in breeding Arabs for speed, and not for those more valuable qualities in which their true excellence lies. Had I continued with my original purpose, I should have lost time and money, and probably have also spoiled my breed, producing stock taller perhaps and speedier, but with the same defects found in the English Thoroughbred.”(see Blunt, Gordon at Khartoum, 2nd ed., London 1912, p. 265)

Although the Blunts gave up the idea of rejuvenating the Thoroughbred with a fresh cross to Arab blood, they continued to register their horses in the Arab section of the GSB, as it was the sole registration authority for Arabian breeding stock in the U.K. GSB registration conferred on the Crabbet horses the advantages of prestige and the eligibility to enter many countries of the world duty free.

Volume IV of The American Stud Book (1884) continued to list Arabian horses imported to America. This volume included the 1879 import *Leopard, the first Arabian brought to America to leave Arabian descent here. The Arabian section in ASB VI (1894) included the imported horses (all from the GSB) of the early breeders Huntington and Ramsdell.

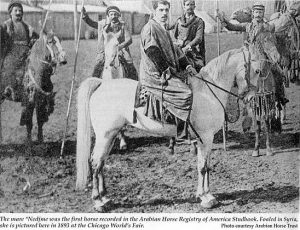

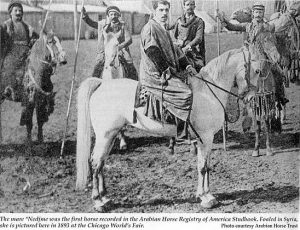

The mare *Nejdme was the first horse recorded in the Arabian Horse Registry of America Studbook. Foaled in Syria, she is pictured here in 1893 at the Chicago World’s Fair.

ASB VII (1898) listed in the Arab section Huntington and Ramsdell horses, with the addition of Ramsdell’s *SHAHWAN, newly imported from the Crabbet Stud, and his mare *NEJDME (spelled “Nedjme” in ASB) from the Hamidie Society’s exhibit at the Chicago World’s Fair. Also included were a stallion from the deserts of Northern Arabia and two stallions imported from Russia for the Chicago World’s Fair. The pedigree information printed with one of the latter, a horse named BEKBOOLAT, states that his second dam was by an imported English Thoroughbred. His pedigree also includes an Orloff saddle mare. BEKBOOLAT’s inclusion in the Arabian section of the ASB demonstrates that at the time the Jockey Club had a rather loose working definition of the term “Arabian.”

ASB Volumes VIII (1902) and IX (1906) list in the Arabian section no newly imported horses other than those which were bred in England, either at Crabbet or by Miss Dillon or Lord Arthur Cecil, and which therefore arrived in this country with GSB certificates. All GSB registered Arabians were automatically eligible for the ASB.

In October of 1906 the S.S. Italia arrived in America carrying 27 Arabians which Homer Davenport had imported directly from the Anazah tribes in Arabia. The only registration authority for Arabian horses in America was the stud book of the American Jockey Club. Not all the Arab horses in America were listed in the Arab section of the ASB. Huntington appears to have ceased registering with the Jockey Club after 1895. The Crabbet bred *IBN MAHRUSS and his dam *BUSHRA appear not to have had ASB registration. Davenport applied for the registration of his new arrivals.

Details of the ensuing embroilment are exceedingly complex, and the full story has yet to come to light. According to testimony published in “That Arab Horse Tangle” (The Rider and Driver, Vol. XXXVIII, No. 11, June 5, 1909 and No. 12, June 12, 1909), the Jockey Club began by sending to Weatherbys for verification the Arabic certificates which had accompanied the Davenport horses. By 1899, “to counter the overt forgery of pedigrees by dealers… the General Stud Book now accepted only Consular Certificates issued in the port where a horse was exported“(James Fleming, writing in Lady Anne Blunt, Journals and Correspondence, p. 407). After a favorable review from Weatherbys, the papers returned to Alexandretta and Aleppo for consular verification, which they obtained. It seemed as though the Jockey Club was ready to register the Davenport horses when negotiations broke down, and the Jockey Club denied the application. Davenport, whose vocation was the drawing of political cartoons, claimed his unflattering portrayal of Jockey Club chairman August Belmont was the cause of bias.

Davenport reminded people that the Jockey Club already had registered several imported Arabians from the Middle East on the basis of documentation ranging from the flimsy to the non-existent. One such mare, belonging to Peter Bradley, was apparently either *ABBYA or *ZARIFFEY, both described as “Kehilan, sub-strain unknown” in the auction catalog from the Hamidie dispersal. Davenport pointed out that their description was useless for establishing purity of blood, and neither mare appears among the eventual registrations of the Arabian Horse Club. Davenport also publicized the Jockey Club’s acceptance of *BEAMING STAR, an unpedigreed animal which Davenport’s traveling companion Jack Thompson had bought on the dock in Beirut and shipped to America on a boat separate from the Davenport importation.

Though registered by the Jockey Club, none of the above animals appears in the Arabian section of the printed ASB volumes. Also conspicuously absent is one of W.R.Brown’s 1918 imports from Crabbet, *RAMLA. This is perhaps because the registrations of foals, and hence to a certain extent their parents, were based on the annual return of breeding records of mares, as were the registrations in the GSB. Since most Americans will not be acquainted with this format, a typical GSB entry is quoted from Volume XXII(1913), p.l 957:

MABRUKA (Bay), foaled in 1891, by Azrek, out of imp.

Meshura, continued from Vol. XXI, p. 896. |

| 1909 b.f. Munira, by Daoud |

Crabbet Stud |

| 1910 b.c. by Rijm (died in 1912) |

| 1911 b.f. Marhaba, by Daoud |

| 1912 barren to Ibn Yashmak |

| 1913 not covered in 1912 |

MARHABA is familiar to American breeders as the dam of the Selby import *MIRZAM (by Rafeef).

Since the Jockey Club refused to cooperate, Davenport joined with other interested Arab horse enthusiasts and formed the Arabian Horse Club (AHC) in 1908. The next year the Arabian Horse Club issued its first stud book, and after certification by the Department of Agriculture, it became the official registration authority for Arabian horses in America. The original 1909 stud book registered 71 Arabians, of which twelve had also appeared in the Arab sections of the ASB volumes published to that date. These horses were therefore “double registered” Arabians.

One Arabian breeder was unimpressed. Though invited to register his horses, Spencer Borden felt no need to do so. His stock imported from England was in the GSB and ASB, the foals he had bred were also in the ASB, and he “did not care to enter them in any other place” (see The Rider and Driver, Vol. XXXVIII, No. 9, May 22, 1909, p. 4). At that point in time, Borden was almost the only one breeding ASB registered Arabians. The registration on the Huntington animals had lapsed, and many of the breeders working with Huntington bloodlines entered their horses in the new AHC stud book. Ramsdell produced an occasional ASB registered foal from one of his *NEJDME mares, but his period of greatest activity as an Arabian breeder had passed. Borden had an effective monopoly on the production of Jockey Club registered Arabians.

Borden’s ultimate goal as a breeder of Arabian horses was to convince the United States Army to use his horses as the basis for an American cavalry stud, producing part-Arab animals for military use. In 1909 he was the only person breeding a significant number of Arabians eligible to the same stud books as Thoroughbreds, and he no doubt saw this as a great advantage.

In 1917, apparently at the insistence of W. R. Brown, Borden relented and “double registered” his horses by entering them in the AHC stud book. Shortly after this, Brown bought out the Borden program, becoming the new monopolizer of double registered stock. In 1918 Brown made a substantial importation from the Crabbet Stud. At the time, Brown’s chief American rival as a breeder was Peter Bradley, whose Hingham Stock Farm had continued to breed the Davenport Arabians after the latter’s death in 1912, as well as horses of Hamidie and one or two other lines. However, Bradley did not breed double registered stock, and the last Arabian foal crop born in Hingham ownership came in 1921.

Brown’s Maynesboro Stud was to enjoy a number of years as the largest Arabian nursery on the continent. He had bought Crabbet bred horses imported by Ames, Borden, and Davenport. He had made his own large importation from that source, followed by a second and much smaller importation from England. He had bought the rest of the Borden herd, which included animals of Dillon, Ramsdell, and Huntington lines. Among the latter was the mare NAZLET, whom Borden had had to register with the Jockey Club himself. Brown also developed a network to keep himself informed of Arabian horses which became available for purchase. After the closeout of the Borden operation and before the 1926 Kellogg importation from Crabbet, Brown was almost the only breeder of double registered stock.

Among the horses Brown’s brother had acquired from the Davenport estate was the 1910 bay stallion JERRED, by the Davenport import *EUPHRATES and out of *NEJDME. Several writers have advanced the theory that JERREDE was not out of *NEDJME, but rather her granddaughter NEJDME III, claiming that Davenport never owned *NEJDME and that the AHC made a mistake in attributing the colt to her. Both Volume 1 (1913) of the AHC stud books and Volume XII of the ASB attribute *NEJDME’s ownership to Davenport, and state unequivocally that JERREDE was her son. Furthermore, as of 1909 NEJDME II (whose sire *OBEYRAN was single registered) was in the ownership of Eleanor Gates in California. Brown was using JERREDE at stud in a limited way, and by 1915 he had begun an effort to accomplish the Jockey Club registration of the Davenport imports *URFAH and her son *EUPHRATES, thus making JERREDE and his get eligible, too. Brown traced a copy of the Arabic document pertaining to *URFAH and *EUPHRATES, secured consular verification of it, and finally had Lady Anne Blunt vouch for its authenticity. The Jockey Club notified Brown of the completion of the registration in 1919. *URFAH and *EUPHRATES appear in ASB XII (1920), on p. 662. Since the credentials of the other Davenport imports were really no different from those of *URFAH and *EUPHRATES, the possibility of double registering them arose. Brown did not want to watch the rest of the Davenport horses ride into the ASB on the coat tails of *URFAH and *EUPHRATES. He insisted that should the Hingham management wish to pursue the matter, the Jockey Club ought to consider the Davenport imports on a case by case basis (see Charles C. Craver III, “At the Beginning,” Arabian Horse News, May, 1974, pp. 97-112). The management at Hingham evidently did not, and the other Davenport animals remained single registered, duly entered in The Arabian Stud Book, but not the Jockey Club Stud Book.

The JERREDE influence endured at Maynesboro only through his daughter DJEMELI (out of Nazlet), dam of MATIH. Other single registered lines from Maynesboro’s early days did not endure, producing their last foals for Brown in 1921. In 1921 and 1922 Brown imported Arabians registered in the French Stud Book, making the last additions to the double-registered gene pool which did not come from the GSB. Brown’s limitation of his breeding stock to double registered animals amounted to a self imposed restriction of his options. Looking from the broadest perspective, that of the development of the breed as a whole in America, Brown’s attitude meant that the separate breeding traditions which Davenport and Borden had established by and large remained separate for another generation. Brown’s horses amounted to a breed within a breed. Since double registration gave his animals an added selling point, Brown and others to follow had a not insignificant economic stake in the matter as well.

Brown made two further importations of Arabian stock to this country: the better known of these is his 1932 importation from Egypt, which included *NASR, *ZARIFE, *RODA, *AZIZA, *H. H. MOHAMED ALI’S HAMIDA, and *H.H.MOHAMED ALI’S HAMAMA. The latter two received their lengthy appellations to distinguish them from Brown’s 1923 import *HAMIDA (Daoud x Hilmyeh) and the mare HAMAMA (Harara x Freda) of Davenport and Hamidie lines. There is evidence to suggest that Carl Raswan helped to steer Brown in the direction of the Egyptian horses. None of the Brown’s 1932 imports appears in the Arab section of the ASB, apparently closed to new non-Thoroughbred registered stock by that time (see below), and since Brown began dispersing his herd shortly after their arrival, it is unclear what use he would have made of them. Brown bred single registered 1934 *NASR foals out of RAAB and BAZRAH. *AZIZA produced the 1935 colt AZKAR, by RAHAS.

Brown also made his own small importation from the desert in 1929. These horses were never registered with either the ASB or AHC. Some believe they never reached this country.

W. K. Kellogg’s importation from the Crabbet Stud in 1926 greatly expanded the base of double registered breeding stock, in terms of numbers and also bloodlines. By that time, the GSB had been closed to newly imported Arabians. The passage of the Jersey Act in 1913 had closed the GSB to Thoroughbreds from other countries, unless they could trace their pedigrees in all lines to animals entered in previous volumes. The 1921 decision did the same thing for Arabians, though one wonders if the death of Lady Anne Blunt in 1917 and the advanced age of her husband, leaving no equal authority, had been an additional factor, making Weatherbys leery of becoming involved in future controversies similar to the one which had surrounded the Davenport horses. Their principal business was the registration of Thoroughbreds, not the verification of the pedigrees of imported Arabians. GSB XXIV (entries through 1920) registered imp. Skowronek, and GSB XXV (through 1924) included imp. DWARKA, the last Arabian added to the GSB gene pool. DWARKA blood had reached America in 1924 in his daughter *ANA. Skowronek blood arrived in the Kellogg shipment of 1926. At about this time the ASB followed suit and ceased to consider imported Arabians not already in the GSB or another Thoroughbred stud book. This established the ASB Arabian gene pool as overlapping that of the GSB with the addition of *EUPHRATES, *NEJDME, and Brown’s French imports. The double registration of the line from *Leopard had not been maintained.

With the advent of manager Herbert Reese in 1927 and the influence of W. R. Brown’s opinions, the management at Kellogg’s came to believe in the importance of double registered stock. Letters in the Kellogg files between Reese and Kellogg indicate that the double registration factor had a major bearing on most aspects of management policy: planning matings, starting young stallions at stud, and the buying and selling of breeding stock. For instance, Reese admired the young sires *FERDIN and FARANA for their conformation, and reminded Kellogg that they had the added advantage of being double registered. Reese made the decision to buy LEILA (El Jafil x Narkeesa) in spite of her status as a single registered mare.

Looking at the Kellogg record from Reese’s arrival in 1927 through 1933, one sees that despite the higher priority attached to double registered stock, the first seven mares Reese purchased and then bred registered foals from had Davenport blood, and that Reese bred more than fifteen foals from double registered mares and single registered stallions. The reason for this is perhaps contained in correspondence between Reese and Kellogg among the Kellogg Ranch Papers. They mention the possibility of registering the ranch’s Davenport stock with the Jockey Club for $50 per head. This writer was unable to locate correspondence to and from the Jockey Club, or any letters explaining why the plan did not come to fruition. Whether Reese and Kellogg, or the Jockey Club, did not follow is not known, but by the summer of 1934 Reese was writing to Kellogg that “…we have eliminated a large percent of the single registered stock” (H.H. Reese to W.K. Kellogg, August 25, 1934). Reese’s last three single registered Kellogg foals out of double registered mares were the 1933 HANAD fillies out of *FERDISIA, *RIFDA, and RAAD. Thereafter, he put Jockey Club mares to Jockey Club stallions only. The fortunes of Davenport blood at the Kellogg Ranch declined as many, but by no means all, Davenport and part Davenport horses were sold. Well known double registered Arabians bred at the Kellogg Ranch include ABU FARWA, FERSEYN, SIKIN, RIFNAS, NATAF, RONEK, SUREYN, and ROSEYNA. Later writers had an unfair tendency to bolster the reputation of these horses at the expense of the ranch’s single registered stock.

As Maynesboro began to break up in the early 1930s, the greatest concentrations of Maynesboro stock accumulated at Kellogg’s, J. M. Dickinson’s, and W. R. Hearst’s. All three breeders continued to double register their horses. Together with the Selby Stud, which had acquired the bulk of its foundation stock from Crabbet, these studs were the principal breeders of double registered Arabians in the 1930’s, and among the largest breeders of Arabian horses in general.

The other major player was Albert Harris, who had bought his first Arabians from Davenport. His foundation sire NEJDRAN JR. and mares SAAIDA and RUHA were all single registered. Harris later added the Davenport import *EL BULAD, a stallion he had tried for years to buy from Bradley before he at last convinced him to sell, according to a letter from Harris among the Kellogg Ranch Papers. Other single registered Harris foundation mares included the Hingham bred MORFDA, MERSHID, and MEDINA. Most of the Harris Arabians were single registered, but he also bred from *ANA, a double registered mare he had imported from England, and a number of double registered mares from Maynesboro: OPHIR, NANDA, *SIMAWA, NIHT, NIYAF, BAZVAN, and MATIH. Harris imported the double registered stallion *NURI PASHA from England in 1924, and had his first ASB registered foals born the next year. With an occasional lapse, Harris proved amazingly conscientious about breeding his few double registered mares to double registered stallions. From 1925 through 1941, Harris bred 38 double registered foals, and only 5 foals from Jockey Club mares and single registered stallions. His Jockey Club mares almost always went to KATAR (Gulastra x *Simawa), *NURI PASHA, KEMAH (*Nuri Pasha x Nanda), KAABA, or KHALIL (both *Nuri Pasha x Ophir) rather than Harris’s single registered sires like NEJDRAN JR., ALCAZAR (Nejdran Jr. x Rhua), and *SUNSHINE. From 1925 through 1931, Harris distinguished his double registered foals by giving them names beginning with the letter “K,” among them the stallions named above. He later abandoned the system: three single registered foals of 1932 and 1934 also got “K” names, and beginning in 1935 virtually all Harris bred horses got names beginning with the letter “K.” In 1942 and 1943 (the last two years in which the Jockey Club registered Arabians as Thoroughbred horses), Harris-owned double registered mares produced five more foals, all by Jockey Club stallions. For some reason, these appear only in the AHC stud book, and not the ASB.

General Dickinson’s farm, Traveler’s Rest, also appears to have used double registration as a guide for making decisions. Most of Dickinson’s double registered horses had come from Brown. Dickinson bred 65 double registered foals born from 1931 through 1942. (Two additional foals, ISLAM and BINNI, were from double registered parents but do not appear in the Arab section of the ASB.) Only 17 Traveler’s Rest foals from the same period were by single registered stallions and out of Jockey Club mares. This seems to indicate that the consideration of double registration had a major effect on breeding decisions at Traveler’s Rest. Jockey Club registered mares were more likely to go to GULASTRA, RONEK, JEDRAN, KOLASTRA, or BAZLEYD than *NASR, *ZARIFE, or *CZUBUTHAN. The matter was of sufficient importance to Dickinson that his catalogs indicate which of his horses carried ASB registration. The consideration may have had a bearing on Dickinson’s decision to sell the Davenport stallion ANTEZ to Poland. Famous double registered Arabians bred by J. M. Dickinson include ROSE OF LUZON, NAHARIN, GINNYYA, CHEPE NOYON, HAWIJA, BRIDE ROSE, GYM-FARAS, and ALYF.

At Selby’s, aside from ten foals out of the single registered mares MURKA, SLIPPER, CHRALLAH, and ARSA, the exception was *MIRAGE. Lady Wentworth, daughter of the Blunts, had taken charge of Crabbet in 1920, and bought this desert bred stallion at Tattersalls in 1923. The 1924 Crabbet Catalog relates that Lady Wentworth was waiting for the completion of additional paperwork regarding his provenance before incorporating *MIRAGE into the Crabbet herd. The writer does not know the outcome of the paperwork, but in 1921 the GSB had closed to imported Arabians, as noted above. Weatherbys registration was of the utmost importance to Lady Wentworth, and unable to induce the GSB to reopen for *MIRAGE, she sold the horse to Roger Selby in 1930.

Britain’s Arab Horse Society (AHS) had formed in 1918 and issued its first stud book the following year; it stood ready to register imported Arabians after the closing of the GSB. However, Lady Wentworth had had a disagreement with the Arab Horse Society, and had ceased to register her horses in its stud book after the 1922 foals. Somewhat like Borden before her, she felt that GSB registration was all her horses needed. It was not until after the War that she rejoined the Society, so *MIRAGE does not appear among AHS registrations.

Selby’s showed little reluctance to breed *MIRAGE and his son IMAGE to double registered mares. The *MIRAGE daughters RAGEYMA and GEYAMA went into the Selby mare band. Of the 64 AHC registered Selby foals born to double registered mares from 1932 to 1943, 28 were by *MIRAGE or IMAGE. However, the management at Selby’s took double registration seriously enough that all eligible Selby foals appear in the Arabian section of the ASB, with the inexplicable exceptions of FRANZA (*Mirzam x *Rose of France) and RASMIAN (*Selmian x *Rasmina). Apparently ineligible was NISIM. NISIM was originally registered as the 1940 grey foal of two chestnuts, namely IMAGE and NISA. After the coat color incompatibility became apparent, the AHC changed the sire to *Raffles. The 1940 entry under NISA in the ASB reads, “covered previous year by an unregistered,” which was standard ASB notation for single registered Arabian stallions used on double registered mares. Famous double registered Arabians bred by Roger Selby include RASRAFF, RAFMIRZ, INDRAFF, SELFRA, and MIRZAIA.

The only Arabian sire getting registered Arabian foals in the first two crops of W. R. Hearst’s stud was the 75% Davenport stallion JOON. By 1935, when the third crop was on the ground, the program had expanded to include the Davenport stallion KASAR and the Crabbet import *FERDIN. The Hearst program was growing rapidly with purchases from the Kellogg Ranch and the disbanding Maynesboro Stud. All of the Maynesboro horses were double registered, but some of the Kellogg purchases were horses with Davenport pedigrees. The Hearst Sunical Land and Packing Corp. began producing double registered Arabian foals in 1936. From that year through 1943, it bred 56 double registered foals, and only five foals from Jockey Club mares and single registered stallions. The key Jockey Club sires at Hearst’s were RAHAS, GULASTRA, GHAZI, and REHAL, all bred at Maynesboro, and the homebred ROABRAH (Rahas x Roaba). Hearst’s also owned and used the Davenport stallions KASAR and his son ANSARLAH, but restricted them in large part to their single registered mares: ANLAH, SCHILAN, LADY ANNE (daughters of Antez), RAADAH (by Hanad), ALILATT (Saraband x Leila), RASOULMA (*Raseyn x *Malouma), and FERSABA (out of the Davenport mare Saba). The other single registered sire at Hearst’s was JOON, but after the management decided to use double registration as a criterion for planning the breeding schedule, apparently the only mare he ever saw was ANTAFA (Antez x *Rasafa). The Davenport influence at Hearst’s, as at Kellogg’s and Harris’s, would likely have been far greater had double registration not been an issue.

Other breeders double registering Arabian foals during the years 1934-1943 included Fred Vanderhoof (from *Ferda and *Bint), E. W. Hassan (from Ghazil), L. P. Sperry (from *Kola and Larkspur), Donald Jones (from Nejmat), C. A. West (from Bazvan), Ira Goheen (from Hurzab and Kokab), L. S. Van Vleet (from *Rishafieh, Raffieh, Selfra, Gutne, and Ishmia), and R. T. Wilson (from Matih). Their combined total of double registered foals was minor compared to the five farms discussed above, but it demonstrates that the concern with double registration and its effect on management policy were not confined to a select group of breeders. At Van Vleet’s, for instance, the Jockey Club mares were more likely to go to KABAR (Kaaba x *Raida) than *ZARIFE.

Until fairly recently, the Arabian Horse Club was inconsistent in assigning the breedership of foals to the owner of the dam at time of covering. Sometimes the breedership of a foal was attributed to the owner at time of foaling. The latter seems to have been the Jockey Club definition of “breeder,” and as a result the breeders of several familiar Arabians differ from ASB to AHC. RABIYAS, e.g., was bred by W. R. Brown according to The Arabian Stud Book and by the W. K. Kellogg Institute according to the ASB.

Some Arabians are in the ASB under a different name. Many of these amount to minor spelling variations, as in the case of HAWIJA (spelled “Hasijah” in ASB). Some take the form of the addition or subtraction of a prefix or suffix. DANAS is “Danas Maneghi” in the ASB, while *CRABBET SURA is “Sura.” Sometimes a numeral was added or subtracted. *Raffles is in the ASB as “*Raffles 2nd,” as there was apparently a Thoroughbred by that name. The mare *NARDA II is in the GSB and the 1906 Crabbet catalog as “Narda,” the numeral apparently added to distinguish her from an American Thoroughbred of the same name. In her case it carried over to her Arabian stud book registration. A few have entirely different names, e.g. RIFDA who is “Copper Cloud” in the Jockey Club Stud Book.

The last Arabians which the Jockey Club registered as Thoroughbred horses were 1943 foals. By the late 1950s, most newer breeders were not even aware that at one time there had been two categories of registered Arabians in America. Very few living Arabians in America show straight Jockey Club pedigrees; this writer estimates fewer than 1%. Among them one would have to include those horses bred from GSB registered Crabbet and Hanstead lines imported from the U.K. in recent decades. The GSB continued to register Arabians through the foals of 1964 and this function helped to a certain extent to hold the older English Arabian lines together as a breeding unit.

The issue of double registration had a controlling influence over the development of the Arabian breed in America. Until the early 1940s, all new breeders had to decide if Jockey Club Arabians were important to them, and if so, to what extent. The double registration factor goes a long way toward explaining why Davenport mare lines were more frequently top-crossed to Crabbet stallions than ASB mare lines were top-crossed to Davenport stallions. The double registration idea continued to influence after 1943, but one cannot know exactly how many breeders based decisions on the possibility of the Jockey Club reopening the ASB to Arabians. Readers are encouraged to examine the pedigrees of their own horses to find breedings selected possibly with double registration in mind.

[A final note regarding Jockey Club registered Arabians pertains to the use of the asterisk(*) to denote an Arabian horse imported to this country. Its first use as such in a printed stud book was in ASB Volume X (1910). The Jockey Club also used the symbol to denote imported Thoroughbreds. It was not until Volume IV (1939) that the Arabian registry adopted its use, though it has recently abandoned it. Arabians imported after June 1, 1983 no longer receive an asterisk as part of their registered names in this country. However, the symbol continues to delight advertisers and pedigree writers; there are no restrictions on its use in these contexts.]

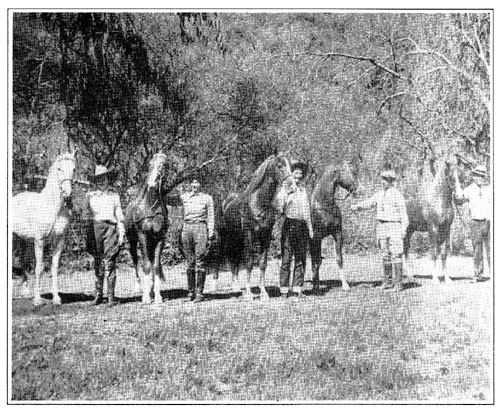

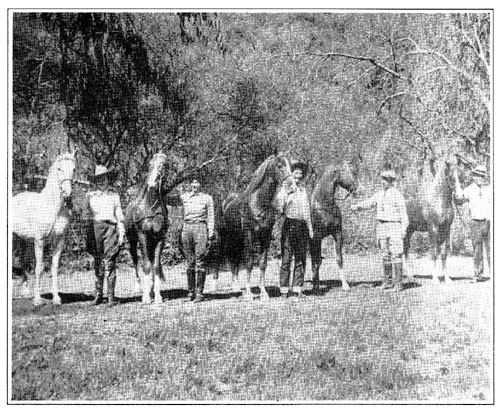

The San Simeon Stallions, 1937: from left JOON, RAHAS, SABAB, GULASTRA, KASAR and GHAZI. Is it a coincidence that they were posed so that the single-registered horses alternated with double-registered ones?

Photo courtesy Harriet Hallonquist.