by Ben Hur (Western Horseman May 1950)

Chicago’s World Fair, 1893, officially known as the World’s Columbian Exposition, was the focal point from which interest in the Arabian horse was created, which eventually culminated in the formation of the Arabian Horse Club of America, 1908. From the importation of 1893 for the exposition, a mare, *Nejdme, and a

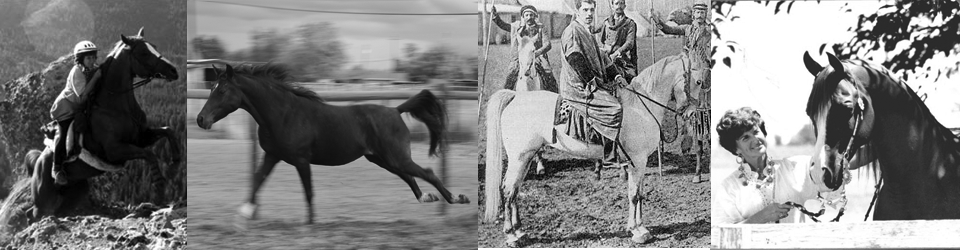

Hadji Hassan, renowned expert on Arabian horses, with *Nejdme. Employed by the Hippodrome Co., at the demand of the Turkish government, he went to the desert and purchased the 11 pure Arabians of the World’s Fair importation.

stallion, *Obeyran, became the No. 1 and 2 Arabians of the official registry stud book. Two other mares and a stallion, several years later, were registered as having come from this importation, although the fact is generally over-looked. They were the mares *Galfia 255 and *Pride 321 and the stallion *Mannaky 294. Offspring of all these have been registered, and they in turn have had offspring until today there is scarcely a breeder who has not had one or more Arabian horses with one of these as ancestor. This tap root, foundation blood, is an important part of the Arabian horses in the United States.

The circumstances under which this importation was made and the many things that happened to it after arrival in this country have remained obscured and unknown to owners of registered Arabians 50 years later. The profound effect and influence which the importation of 1893 had upon certain individuals who obtained some of these horses, imported others and later formed the registry club, is a fascinating story. The story, with the simple trust of the Bedouins, the deception, greed and duplicity of its promoters, avarice of the quick acting Chicago loan sharks, dire want and hunger, fires, theft, abandonment and final breakdown of the entire enterprise and the sale at auction of the remaining horses, would make a movie scenario for today of triple A rating.

This account will raise a doubt in the minds of many of the the correctness of the foaling dates of *Nejdme and *Obeyran in the

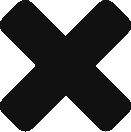

*Obeyran No. 2, grey stallion, came into the possession of Homer Davenport, who took this picture and under it, in his booklet, 1908, titled him “The best horse in America at 28 years old.” Was Davenport mistaken about his age?

stud book and to which of the mares the name Pride (apparently a stable name) really belonged, since this account and the auction sale listed no such mare named Pride. As in a modern mystery story, the reader may draw on his powers of deduction, but arrive at two entirely plausible, conclusions, and in the end the purity of breeding of none, regardless of names, has been challenged, although the original desert family strain may remain in doubt.

The Arabian registry stud book lists the foaling date of *Nejdme No. 1 as 1881 (in the desert), of *Obeyran No.2 as 1879 (in the desert). The same stud book credits *Nejdme with 13 foals registered, the last foaled in 1913, Seriha No. 320, when she would have been 32 years old, if the stud book foaling date is correct, a most unusual, late date for a mare to give birth to a foal. The Turkish member of the World’s Fair commission, who is authority for this account, lists *Nejdme as having been foaled in 1887, a more plausible date, but he contradicts this date. What are the facts?

Invitations had been sent to every country on the globe to participate in the exposition, to build a building and show products from their country. The coming fair was the topic of conversation everywhere. A Syrian in the employ of the ministry of agriculture of Turkey conceived the idea and, through the influence of the first chamberlain to the Sultan, received a concession from the Turkish government to take a troupe of Bedouin horsemen to Chicago. (Syria, Lebanon, Arabia, the Holy Land, were all protectorates of Turkey.) The request was at first refused, but the Sultan was made to believe that the proposed enterprise was intended more as an exhibition of pure bred horses than as a show, and on this belief the concession was ordered granted under strict conditions:

- None but the purest bred, pedigreed horses should be taken;

- All the horses to be returned back to the desert;

- The riders to be the best horsemen from the several friendly Bedouin tribes;

- Two cavalry officers to accompany the troupe to supervise everything and see that the contract, which contained 52 such conditions as the above four, was complied with.

The granting of the concession made a great sensation in Constantinople, and in less than two days the money asked for—25,000 Turkish liras ($112,000)—to carry on the enterprise was subscribed exclusively by Syrian capitalists in Constantinople, Beirut, Paris and Egypt. Raji Effendi, promoter and holder of the contact, was offered $15,000 spot cash, a free trip to Chicago and back, all his personal expenses for six months, which he indignantly refused. He remained in the company and, in the end, penniless, the Turkish government paid his passage back home.

The company was made up of men who might have been shrewd business men in dealing with the simple and confiding Bedouins of the desert, but who had no idea of American business methods, much less Chicago methods at the time of the fair. They thought 25,000 liras ample. They chartered a Cunard steamer and with 120 men, women and boys, 45 horses, 12 camels, donkeys, fat-tailed sheep, Oriental cracked wheat, oil, butter, cheese, flour, an immense quantity of barley, half a ton of horseshoes and boxes containing 1 1/2 million $1 admission tickets, set sail for America. Among the men were all the stockholders, each having one or more servants, riders, donkey boys, camel riders, seven cooks, five horseshoers, 15 clerks and ticket sellers—everybody who begged to be taken over was put on board.

They arrived in Chicago penniless. They had hardly settled and pitched their tents at the baseball grounds before one Chicago load shark loaned them money at an exorbitant rate of interest and took a mortgage on all they had, horses, donkeys, camels, tents and wearing apparel. Another individual had himself hired as manager of the show at an enormous salary with an iron-clad contract. Still another made a contract to become attorney of the corporation at $600 a month salary. All this happened within the short space of 30 hours after their arrival.

They moved to Garfield Park: Chicago creditors were upon them like hungry vultures. A fire, certainly of incendiary origin, drove them back to 35th street. In this fire they lost seven horses, some of the camels and 15 trunks of clothing. Finally they moved to the Midway at the fair and gave their first performance on the Fourth of July, 1893. The show was widely advertised as the $3 million Hamidieh Hippodrome Co., named after the Sultan of Turkey.

To the fair came people from all parts of the world. The Bedouin show with the beautiful horses attracted wide attention. From England came Rev. F. Vidal, Arabian breeder and authority, in company with Randolph Huntington, Oyster Bay, L.I., N. Y., who had purchased and imported *Garaveen, bred by Rev. Vidal, and later *Kismet, sire of *Garaveen.

Also to the fair came J.A.P. Ramsdell, Newburgh, N.Y., who later succeeded in obtaining *Nejdme. Peter Bradley, Bostonian industrialist, Hingham, Mass., was another deeply interested visitor to the Midway Bedouin show, who from that time on began his attempts to acquire Arabian horses. Probably the most far-reaching effect of the Chicago World’s Fair importation, however, was made on a newspaper cartoonist, who stood on State Street, Chicago, and saw the Bedouins and their steeds parade by. From then on, it became a life ambition for the newspaper cartoonist, Homer Davenport, to go to the desert and bring back Arabian horses. He achieved his ambition with the financial assistance of Peter Bradley as a partner with his importation of 1906.

During the fair it was hinted by informed observers of the horses that a number of them did not show the true characteristics of the pure Arabian horse. A cloud of uncertainty and mystery gathered about the hoses with the passing days. Finally in 1897, after the remaining horses and effects had been sold at auction and the last deluded, miserable Bedouin had been sent home, a member of the Turkish World’s Fair commission was prevailed upon to make a written, public report on the entire enterprise. A copy of this report was printed in The Horsemen, Chicago, June 15 and 22, 1897, and a copy was sent to Peter Bradley.

More than 30 years later, in a visit with him, he recalled the report and gave the copy and other data to the writer. In the report, the author, A. G. Asdikian, wrote:

I came in daily contact with these men, fed them at the expense of the commission when they were hungry, helped them who were now and then driven out of the camp for fighting, a frequent occurrence. I knew every man, woman and boy by name, and there was no question that they would not answer for me as to the origin and history of the horses.

Among them was Hadji Hassan, pure Anazeh Bedouin, who all his life had been a horse dealer among the desert tribes. He was at several times employed by the Turkish government to purchase cavalry horses. From Aleppo to Egypt and Yemen he was known as the best judge of Arab horses in the country. The Hippodrome Co. hired him at the demand of the governor of Beirut in order that the horses purchased should be of purest blood. The company sent him among the Anazeh tribes, and 11 horses of the 45 brought to Chicago, were all that Hadji Hassan bought. These 11 had the customary written pedigrees, which I saw, read and took note of. I will say that these 11 horses were among the purest bred Arabs that ever went out of the desert.

When the troop landed in New York the U. S. Customs authorities levied a duty of $30 on each horse, the supposition being that the horses did not belong to any of the five pure, desert families, as stipulated and exempted in the McKinley tariff law. After their arrival in Chicago I learned of the 11 horses with pedigrees and suggested to the commissioner general to make application for refund. They could not be persuaded to forward the pedigrees to Washington without security.

Advice being to no avail, we threatened to sue them and secure the pedigrees. They promised to deliver them the next day. I went to Garfield Park to get the documents as agreed, and to my surprise could find none of the directors in the camp, but knowing the Bedouin in whose care the papers were left, I demanded them. The poor old man, with tears in his eyes, begged me not to take them from him, as the directors had told him they would turn him out of the camp if he ever parted with his trust. In order not to embarrass him, I promised not to take them from him if he would show them to me. He produced a batch of 10 pedigrees from his trunk, and I read every one of them by the assistance of one of the clerks who could speak Turkish, and wrote down as much of them as would enable me to prepare an application to be forwarded to Washington. When I had finished this work, I had this man and Hadji Hassan show me the pedigreed horses. From this time on I knew which of the horses were pure Arabs. I never again saw these documents, the claim being made that they were destroyed in the fire together with 34 other pedigrees which I did not see, as they did not exist. Against the accusation of the commission that they did not live up to their contract, these shrewd Syrians claimed that the documents were lost in the fire, an absolutely false claim, which we were powerless to contradict.

To make themselves more secure they showed us a voluminous document signed by the governor of Beirut, who certified that the men had been faithful to the conditions of their contract. Of course we knew how this certificate was procured—by bribery and trickery. The trick was this: It appears that at the start they brought from the desert to Beirut these 11 horses, some camels, donkeys, fattailed sheep and Syrian goats. They represented they were going to make a livestock exhibit at Chicago. The pedigrees of the horses were submitted to the governor to convince the authorities that the troupe would be organized in compliance with all the conditions of the concession. After securing the governor’s signature they purchased such mongrel horses as would the best answer the purposes of the proposed show. The horses were finally sold at auction at the Chicago Tattersalls, January 4, 1894. I prepared this descriptive list from a notebook which I kept for the special purpose of writing down all I learned and heard about the horses.

At the Chicago Tattersalls sale, 28 remaining horses were numbered, listed and catalogued by number. (From this list of 28 in the Asdikian report we omit all but the pure Arabian.) There were 7 pure Arabian, as follows:

No.1 Nejdme, grey mare; 14 3/4 hands, foaled 1887; breed Kehilan-Ajuz

2. Kibaby, grey stallion; 14 3/4 hands, foaled 1885, Seglawi-Sheyfi

7. Obeyran, iron grey; 14 1/2 hands, foaled 1889, Seglawi-Obeyran

13. Halool, bay stallion; 15 1/4 hands, foaled 1886, Kehilan-Ras Fedawi

24. Hassna, dark bay mare; 14 3/4 hands, foaled 1889, Managhi-Hedrij.

26. Galfea, sorrel mare; 14 1/2 hands, foaled 1887, Hamdani-Simri

28. Manakey, sorrel stallion; 14 3/4 hands, foaled 1888, Managhi-Slaji

I can say that the choicest of the lot in this sale went to Boston, purchased by H. A. Souther, who was commissioned by a Boston gentleman to buy some of the horses at any price. By purchasing the stallions 7, 13; 28, this gentleman (Mr. Bradley) secured the plums of the lot, except the magnificent stallion, Kibaby, No. 2.

Among the mares the grey Nejdme took the palm. For a long time her pedigree was kept by Hassan, and after the old man left Chicago it passed into the hands of one of the clerks, who refused to return it until his wages were paid. Scores of times I saw this document and read it. She was “a pure Kehilan of the purest and belonged to the Ajuz sub-strain.” For many months it was a puzzle to me why this magnificent pure bred mare was ever sold to go out of the desert. Was she stolen? Hassan said “No,” because he got her from her owner at 900 Turkish liras ($4,200). Whenever I asked this question Hassan was as mute as a clam. “If you people know anything about horses, watch and find out,” was all he would say. I did watch day and evening for over six months but could see nothing wrong with her. She was as sound as a “new milled dollar.” About three weeks after the fair, while the men were still lingering around. I noticed that Nejdme was in heat. I called my old friend Hassan and asked if I was correct. He said, “Yes, that mare has been coming in heat for five years.” It was plain now. When three years old she had one colt but she could not be settled in foal again. At that time she was eight years old. This was the reason Nejdme was sold to be taken to this country. The first offer for her was $3,500 but the directors refused to sell. The mare had attracted so much attention that the price put on her was $10,000. The second offer made in late October was $2,700, which was also turned down. Finally I purchased the mare for a New York gentleman (Mr. Ramsdell), paying $450 down, but before I could take possession she passed into the hands of the sheriff and I was out $450, as I could neither find the men to whom I paid the money nor could I get the mare. At the auction she was purchased by the receiver, who sold her afterwards for $800 to the same gentleman for whom I had bought her previously. After being told the mare could not be settled in foal I still bought her for my friend because I believed that she could be settled if intelligent methods were used and the mare properly cared for, That she had foals since shows that I was not mistaken in my judgement.

The registry of 13 foals out of *Nejdme in the stud book here, amply supported the judgment of Mr. Asdikian, that with intelligent methods and proper care she would raise foals. His notes and the Tattersalls sales list her as foaled 1887. Yet he states she was eight years old at the time of the fair, 1893, a discrepancy of two years. It would be easy to mistake an old-fashioned 7 for 1 and vice-versa. All the evidence would indicate 1887 the correct date rather than 1881 as her foaling year. Her last foal in 1913 would be at the age of 26, rather than 32.

Dahura No. 90, important and prolific early Arabian mare, granddaughter of *Nejdme. Dahura raised her 19th foal at Ben Hur farms when 25 years old, died at 29.

It will be noted that the name Pride did not appear in the notebook kept by Mr. Asdikian nor does he report the name in the Tattersall sales. Where did the name originate and to what mare of the importation did it belong (as a stable name). All will agree this English word was not the original name of one of the desert-bred, 1893 importation. The original application for registry gives little light on the subject. Date of foaling of Pride 321 and Galfia 255 are listed in the stud book as “unknown.” The 1918 volume of the stud book records Homer Davenport as owner of both Galfia and Pride. He had died in 1912, which may account for the meager registry data on these mares which should have been recorded among the first in 1908 with Nejdme and Obeyran. Mr. Asdikian describes Galfia as a “sorrel mare, one fore and both hind feet white; Hamdani-Simri,” Pride is also recorded as a chestnut or sorrel), but a Managhi-Slaji. If she was a chestnut, then Galfia and Pride were one and the same mare. If she was a Managhi and a dark bay she could have been the No. 24 mare Hassna noted in the sales list as a Managhi-Hedrij. The conclusion would be obvious that it would be harder to mistake identity between a chestnut and bay than it would be to become confused and mistaken with desert strain names. Thus, owners of Arabians can form their own conclusions of the correctness and value of some of the early strain names in some of their present day Arabians.

The Tattersalls sale list, as reported by Mr. Asdikian, gives the foaling date of *Obeyran as 1889, while the stud book lists him as foaled 1879. By what authority was Davenport led to believe him 28 when he took the picture? Or was he really 10 years younger? Finally, would Hadji Hassan, the expert on Arabian horses, buy for this strenuous trip and exhibition a 14-year-old stallion or a four-year-old; a 12-year-old mare or a six-year-old?